Let’s be brutally honest here; when it comes to gardening, there is often a lot of humble bragging and over-fertilized egos involved.

“Oh, you aren’t entirely organic? Hmm. That’s…interesting.”

“We only use compost that we make ourselves.”

“I have an eight-step rotating cover crop system I implement each fall, followed by a vermicompost tea soil drench that I apply six times in the early spring starting in February. What do you do?”

“Um, plant vegetables. In the dirt. In my backyard.”

I’m here to alleviate some of your gardening guilt today. It’s okay if you don’t rotate your crops.

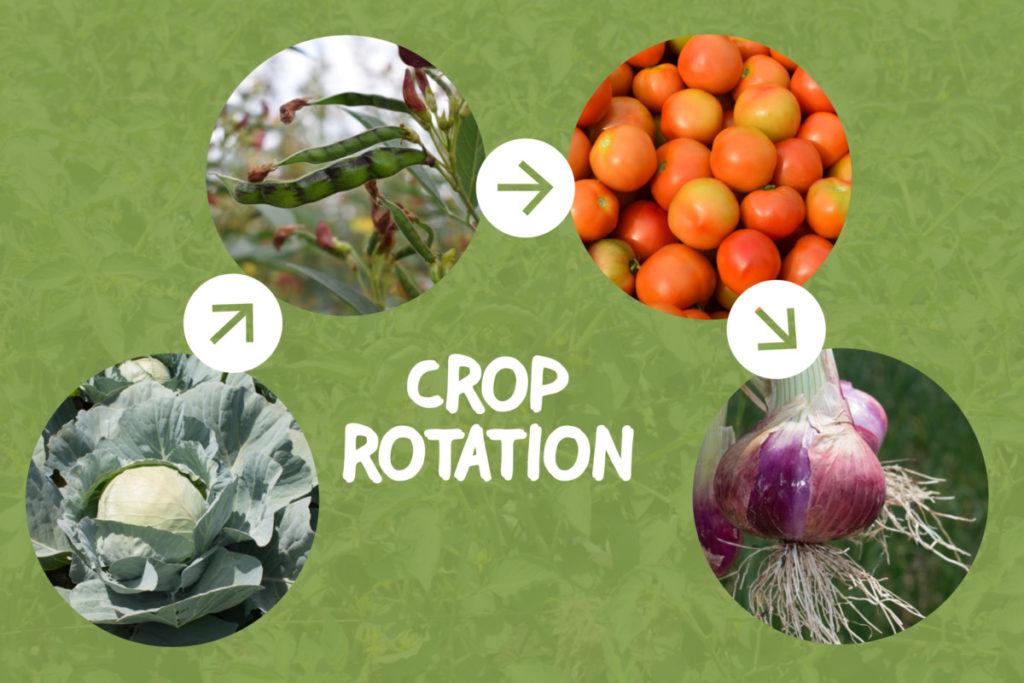

If you’ve been at this whole gardening thing for a while, then you’ve likely heard about crop rotation. Lord knows every gardening website on the Internet has an article or two about its benefits, including Rural Sprout. (It’s kind of obligatory in the gardening world, much like plugging the benefits of going organic.)

A few years ago, I took a closer look at the practice and its application in the home vegetable patch. After unearthing the origins of crop rotation, I decided it wasn’t worth my time, and I haven’t looked back.

Why I Stopped Using Crop Rotation in My Garden

I’m a fan of the KISS principle in all aspects of life: Keep It Simple, Stupid.

For me, crop rotation ends up being a lot of extra work with no measurable benefit. So, I stopped. It’s just not worth the time and effort. From a commonsense perspective, well, it’s not.

Every January, I would sit down to plan out my garden, and it was always the same headache.

Where do I move everything so that nothing is planted where it was last season and it’s in the right rotational order?

Well, if I move the tomatoes over there, then that means I have to build something to support them instead of letting them grow up the fence.

And if I don’t put the pumpkins in the extra-large row, then they’re going to creep into the walking paths.

Shoot, if I move the lettuces down there, then I have to move the polytunnel as well.

Home gardens are too small to make crop rotation anything but a headache. There are better ways to care for the soil in your garden.

The problem with crop rotation is that it was never meant for home gardeners. It’s been a practice meant for large-scale farming right from the beginning.

Where Did Crop Rotation Come From

As early as 6000 BC, farmers figured out that alternating crops (between legumes and cereals) made for more productive soil and better harvests. It’s had numerous iterations through the years, starting as a two-field system where you swapped crops every year. There was also a three-field system, which was the same as the two-field system, with the addition of one remaining fallow for a season.

And finally, in what is now Belgium, the four-field rotation system that’s so common was developed in the late 1600s.

Note the operative word in all of these examples – field.

These days, crop rotation is an absolute necessity in commercial farming. The harsh practices of this kind of large-scale farming – growing mono-crops on acres of land, dumping chemical fertilizers, pesticides and herbicides on the soil, and tilling year after year – have pushed the soil to the brink. It’s only through crop rotation that we still manage to get something to grow.

Clearly, things need to change in the commercial realm if we intend to continue to feed the planet.

However, from its inception, crop rotation has always been for farming mono-crops on large swaths of land to feed an entire population.

How it crossed over into home gardening is anyone’s guess. It’s likely people started adopting it after watching the farmers. The problem is, it doesn’t make sense for a home garden.

Why Are We Supposed to Rotate Crops?

Crop rotation is meant to help with overall soil fertility as well as pest and disease suppression. When you grow the same crop in large areas, it’s called monocropping. That’s basically how commercial farming works. They grow the same crop in a large field. That crop uses a specific combination of nutrients from the soil to grow. If those nutrients aren’t replaced, then it makes it harder to grow subsequent crops in that space.

If this pattern continues over the years, then the soil health plummets, as we see now in commercial farming.

By monocropping in the same space, you’re also attracting the same variety of pests over and over again, making it harder to grow the crops they’re attracted to. And if things such as blight or soil-borne diseases occur, it’s that much harder to get rid of them.

Crop rotation makes a lot of sense for large-scale farming. In fact, the entire industry can do much better than crop rotation with regenerative farming and polyculture practices, and they need to.

But when it comes to rotating crops…

Size Matters

On a much smaller scale, such as in a home garden, crop rotation doesn’t make a whole lot of difference. For starters, you aren’t growing a monocrop. Most of us grow more than one vegetable each year. We aren’t covering acres of land with a single crop. We’re growing numerous vegetables in a matter of a couple hundred square feet or less.

It’s much easier to replace lost nutrients each season in a small home garden than it is on a large scale.

In fact, most of us do this already by adding compost, mulch or other organic matter each year, making crop rotation unnecessary. No-dig gardens, using cover crops or green manure, and chop-and-drop fertilizers are all easy ways we replace nutrients. So our soil is continually improving, season after season.

Not to mention, we home gardeners have a bad habit of fertilizing without testing our soil first to see if it’s even necessary.

In your average organic raised bed or home garden, it’s more likely that we’re over-fertilizing rather than growing in nutrient-depleted soil.

But What About Pests?

Look, I’m just going to say it – rotating crops in a small home garden does diddly squat for preventing pest buildup. I moved my kale and cabbages from one row to another every year, and unsurprisingly, the imported cabbageworms would still find them.

The flea beetles still found my eggplants, the Colorado potato beetles still found my potatoes, and the leaf miners still found my spinach.

Why? Because moving a crop a few yards from where the pest is overwintering in the soil isn’t far enough to make a difference. It’s much the same for plant diseases.

Moving crops a few yards away isn’t an effective way to mitigate these types of issues.

Instead of crop rotation, these days, I practice good soil hygiene. It’s much easier and less hassle. And, as I’ve already pointed out, most gardeners are doing it anyway. Here are a few tips to ensure you have healthy soil without the hassle of playing musical crops each year.

Skip the Crop Rotation and Do This Instead

Inspect your garden

Once a week, I walk around my garden, slowly admiring everything that’s growing. I don’t worry about weeding or picking produce. I’m keeping an eye out for pest damage or the first signs of disease. Doing this allows me to get ahead of both by catching them early. It’s also a great way to relax and slow down during a busy week.

Dispose of Diseased Plants

I don’t mess around with diseased plants. Because my garden is small (around 1,000 square feet), I know how quickly things can spread. If there are signs of disease present, but it’s only on a few leaves, I’ll cut out those leaves. If the disease has started to spread, I will remove the plant and burn it. (Never compost diseased plants.)

Pests

Pests I handle similarly to disease, but it depends on what exactly is eating my crops. I was hit by squash borers last year. Rather than take the chances of them wintering over in the soil, I yanked every cucurbit up and burned them all. I would rather buy my cucumbers and squash at the farmer’s market for the rest of the summer than host those pests for another year. However, for things like cabbageworms, I usually ignore them. Once the weather cools, they die off, and I end up with plenty of kale and cabbage.

Till the Garden Only As Necessary

I switched to no-dig gardening a few years ago with great success. However, after a few years the abundance of pests wintering over in my soil got to be out of hand. Moving my crops didn’t help. So, I decided to till my garden in the fall and again in the spring before planting. It disrupted many of the overwintering pests and helped a great deal. To be clear, I don’t till every year, only if there is a large pest load in the soil.

Add Organic Matter Throughout the Year

When I plant in the spring, I work some compost into the soil. Leaf mold is a great option, too. I add a new layer of straw mulch each year, leaving the old to break down in place.

I grow borage throughout the garden, which pulls in pollinators like a magnet, and then “chop and drop” it. (It’s happy to self-seed, so I rarely bother to plant it anymore.) And at the end of the season, we rake the leaves from our oak tree into the garden.

Test Your Soil, Test Your Soil, Test Your Soil

I refuse to get off my soapbox on this one. I mention testing your soil in almost every Rural Sprout article I write because it’s so important for soil health, and so few gardeners bother to do it.

Most of us are guilty of adding fertilizers to our soils without having a clue as to whether or not they’re needed. It’s such a bizarre practice when you think about it. We assume our plants need to be fertilized, but we have no clue what nutrients are actually in our soil. Test your soil at the beginning and the end of the season. You’ll know if your soil needs anything and what, rather than guessing.

Switch to a No-Dig Garden

While this isn’t completely necessary, and it isn’t for everyone, no-dig gardens are so much easier to take care of. Not to mention, you’re constantly improving the soil with no-dig gardening.

And that’s that. I’m sure most of this is stuff you already do or have heard of. That’s the point, though. Most gardeners are already doing things that replace nutrients and improve their soil, which is more than can be said for the commercial farming industry. So, skip the crop rotation and make gardening just a bit easier and less time-consuming.

Get the famous Rural Sprout newsletter delivered to your inbox.

Join the 50,000+ gardeners who get timely gardening tutorials, tips and tasks delivered direct to their inbox.