At first glance, plants might appear totally helpless against insects, herbivores, and other leaf-gobbling predators.

Like sitting ducks, plants are rooted in one spot so they can’t do the whole fight-or-flight thing other creatures rely on to survive.

Although they can’t uproot themselves and scurry to safety at the first sign of trouble, many plants do have a litany of deterrents at their disposal.

Plant Defenses are Diverse

The most visible ones are the thorny, spiny, prickly plants with razor-sharp stabby bits – like roses, raspberries, cacti, and thistles – that will deliver painful pokes and scratches to any animal that comes too close.

Other defensive maneuvers are more subtle. For instance, corn and wheat will take up silica from the soil to harden the leaves, making the foliage tougher for grazers and insects to chew.

Or, cleverer still, are the flowers that ramp up their nectar production to call in reinforcements. Ants and wasps will be drawn to the sweet scent of nectar, and these will serve as the plant’s protectors by preying on nearby insects.

For larger predators like us, mishandling the wrong plant can unleash the plant’s chemical defenses, causing the skin to break out in rashes, hives, blisters, burns, and other uncomfortable skin conditions.

You’re probably already familiar with poison ivy, poison oak, and poison sumac – and the old adage “leaves of three, let it be” – but there are a few others you should be wary of in your travels.

Chemical Warfare in the Plant Kingdom

Quite a large number of plants use chemical defenses to protect themselves. The list is long, but the good news is, in many cases, you’d need to actually ingest the leaves to have a reaction.

There are a myriad of plant species, however, that activate their chemical defense mechanisms as soon as they are disturbed. They might not have any brains, yet plants can sense being touched and will communicate danger to other plants by releasing pheromones into the air. Nearby plants, in response, will switch on their own internal defenses.

Simply brushing against the foliage of some plants causes the release of toxins that can enter the epidermis without requiring a break in the skin. Once absorbed, the plant sap or oils trigger itchy, blistering rashes anywhere from 2 to 10 days after contact.

Others exude phototoxic sap that doesn’t do any damage on its own. But when the plant chemicals are exposed to sunlight, the skin erupts with burning, swelling, blistering, and itchy red spots.

Sometimes, the noxious chemicals are emitted into the air and enter the body through the eyes and nose.

And then there are plants that double up on defenses. These types have what look like tiny hairs all over the leaves and stems, but these are actually sharp hollow needles filled with chemicals.

8 Plants that Can Irritate the Skin

It’s always a good idea to know which plants to avoid before heading out into the wilderness to forage, hike, or camp.

But weeding an overgrown patch in your yard can have you coming up against plants that should be treated with caution as well. After all, every spring will bring with it a deluge of fresh weeds to pull, sprouted from seeds dropped by birds or carried in with the wind.

For those with sensitive skin, even working in the flower or vegetable garden can hold hidden dangers.

1. Poison Hemlock

Poison hemlock (Conium maculatum) comes from the carrot family and looks almost identical to wild carrot or Queen Anne’s lace.

Like its doppelgänger, poison hemlock blooms with large, flat-topped umbels (umbrella-shaped flowers) composed of tiny white flowers in late spring. It has bright green fern-like foliage and can grow to be 2 to 8 feet tall. When the leaves of poison hemlock are crushed, they emit a very strong musty odor.

The easiest way to tell wild carrot and poison hemlock apart is to look at the stem. Where wild carrot will have stiff stems covered in coarse hairs, poison hemlock stems are hollow and hairless, with distinctive purple or reddish splotches and streaks.

The greatest worry with poison hemlock is misidentifying it as wild carrot or parsley and eating it by mistake. This can be a fatal error because all parts of the plant – leaves, stems, roots, and seeds – are extremely poisonous to people and animals, even in small amounts.

Although touching the foliage of poison hemlock won’t trigger skin rashes and blisters for most people, the toxic alkaloids can enter the bloodstream through the eyes and nose, as well as in any cuts or openings in the skin. The danger of poison hemlock is long-lived since dead canes can stay toxic for up to 3 years.

The level of toxins in poison hemlock sap varies but is typically highest when plants are growing in a sunny location. There have been reports of gardeners who had a severe reaction after pulling plants on hot days because the toxins got into the air and were absorbed into the skin.

2. Giant Hogweed

Giant hogweed (Heracleum mantegazzianum)is another member of the carrot family and possesses the same characteristic traits as its cousins in the Apiaceae genus – deeply lobed feathery foliage and white umbel flowers that appear from June to July.

But giant hogweed does indeed become humongous, and mature plants are easier to identify. Plants can reach 20 feet in height, with a leaf span of 5 feet across, and flower heads that measure 4 feet in diameter.

Younger specimens can be recognized by their purplish splotches – similar to poison hemlock – but with the addition of white hairs along the stems.

Giant hogweed is a formidable plant with robust phototoxic defenses. The sap causes painful burning blisters and scarring where it gets on the skin and then is exposed to sunlight.

If the toxic ooze gets in the eyes, it can be temporarily or permanently blinding.

3. Parsnip

Whether it’s cultivated in the garden or encountered in the wilderness, parsnip (Pastinaca sativa) is another carrot relative that can be just as mean.

Parsnip foliage is yellowish-green in color, with a central stem that bears 3 to 5 toothy, pinnate leaflets. The stems are mostly hollow with vertical grooves running up and down the length. Reaching up to 5 feet tall in its second year, parsnip blooms from June to mid-July with clusters of teeny yellow flowers in loose umbels.

Though the cream-colored taproot is a tasty edible, the leaves and shoots of the plant contain phototoxic sap that, when combined with UV light, leaves weeping blisters and burns in its wake. The affected areas of the skin can remain sensitive and discolored for up to two years after initial contact.

Severe reactions to parsnip are fairly rare but it’s still prudent to take a cautious approach when handling the plant.

To minimize the risk of burned hands and skin, avoid touching parsnip foliage on sunny days and pulling up plants after they’ve gone to seed. After harvesting the taproot, always wash up thoroughly to remove any plant sap that might’ve gotten onto the skin.

4. Stinging Nettle

Stinging nettle (Urtica dioica)is a perennial herb that grows on erect stems that can reach up to 9 feet high. It has pointed opposite green leaves with saw tooth margins.

It’s considered a noxious and invasive weed in many places, spreading via underground rhizomes that can quickly become dense colonies.

The leaves and stems of stinging nettle are covered in tiny hairs that act like hypodermic needles. Wherever the plant touches skin, it pierces and injects several inflammatory chemicals, including histamine and formic acid. The stinging sensation will be felt immediately upon contact, later developing into hives.

If you find yourself on the wrong side of a stinging nettle, don’t touch the rash for the first 10 minutes. Rubbing or scratching the area can push the chemicals deeper into the skin. Use soap and water to gently wash away the toxins. Any stingers still stuck in the skin can be pulled out with sturdy tape or wax strips.

Despite its reputation for painful jabs, some gardeners intentionally cultivate stinging nettle in their gardens. Mind the foliage, and it can be an incredibly useful plant. The leaves are nutritious and taste similar to spinach; just make sure you boil or steam it to remove all the stinging bits first. You can also use it to make a natural fertilizer.

5. Rue

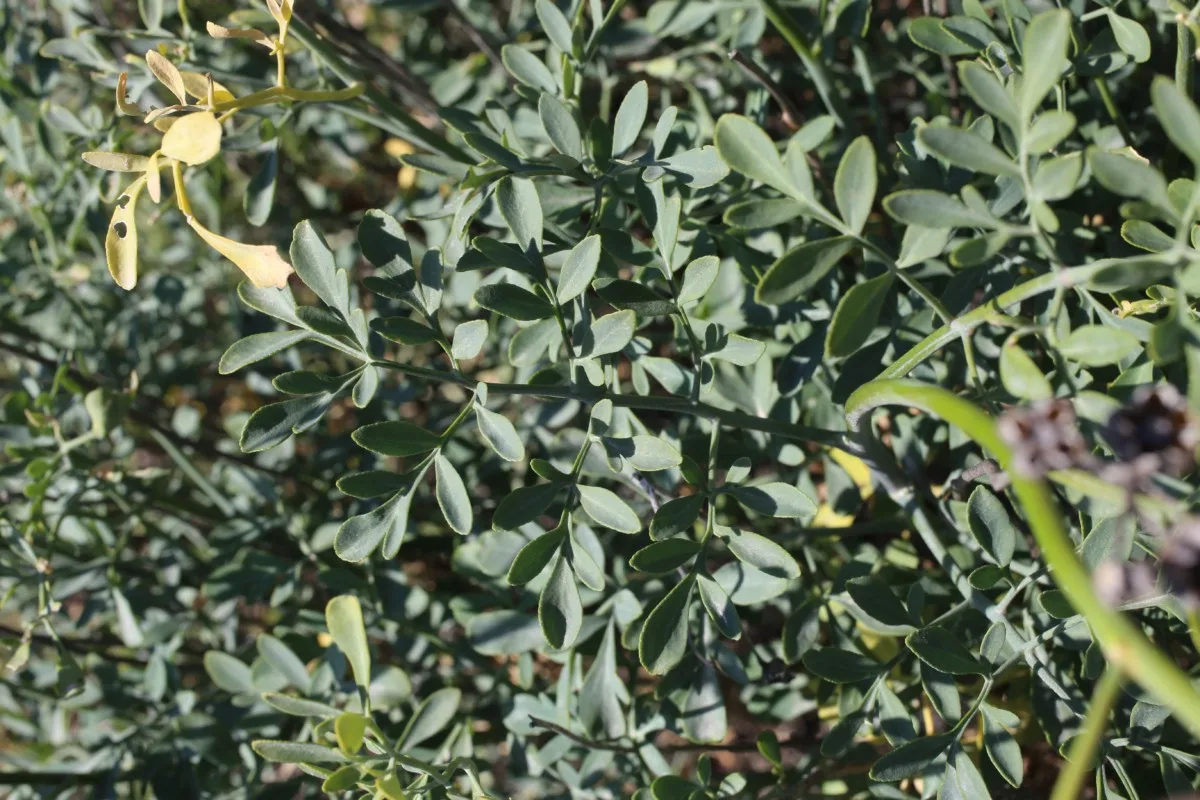

Rue (Ruta graveolens) is a pretty herb, noted for its deeply lobed, delicate blue-green leaves and shrubby habit. In spring, it blooms with clusters of small yellow flowers.

It has a long history of use as a medicinal plant and as a culinary spice – but only in very small amounts.

The acrid leaves are poisonous, and the whole plant emits a musty odor most find unpleasant. But it’s the strong smell of rue that makes it so effective for repelling pest insects and grazing critters.

Don’t rue the day you crossed rue, though. The sap contains an array of toxic compounds that can burn the skin when exposed to sunlight. Handling or brushing up on the plant on a sunny day may leave you with burned and blistered flesh.

Keep rue plants at a safe distance at the back of borders, away from paths and other high-traffic areas. Handle the plant foliage only in the evenings and on cloudy days to lessen the phototoxic risk.

6. Tomatoes

Anyone who has grown tomatoes knows they have a very distinctive aroma.

The earthy, spicy musk that tomato plants give off is due to volatile oils stored at the ends of their hairy stems and leaves. When the foliage is disturbed, the oils are released. The scent helps keep pests away, but can also affect people who are sensitive to these chemical compounds.

You might be able to eat a tomato without trouble, but handling the foliage can deliver itchiness for days. The coarse hairs that cover the plant can be irritating too, and the skin can sometimes react by breaking out in red, swollen, itchy patches.

Fortunately, getting a rash from tomato leaves isn’t too common. But if you find you have red and itchy skin after tending your tomato plants, you should cover up before heading into the rows. Don’t work in the plot on sunny days, and wash up well as soon as you’re done.

7. Cucurbits

Squash, melons, cucumbers, zucchini, pumpkin, and other members of the cucurbit family have been known to cause an adverse reaction for more than a few gardening enthusiasts.

Like tomatoes, it might not be an allergy per se if you can still enjoy the fruits without feeling a burning or tingling sensation in the mouth.

Aside from belonging to the cucurbit clan, what these vining plants have in common is foliage covered with prickly hairs. And for some folks, that leads to an itchy red rash that appears immediately after working with the plants. Thankfully, it goes away after a few hours.

Cucurbit rashes can affect the arms and hands but can also appear on the face, neck, and chest. When plants are disturbed, the small prickles on the leaves can break away from the plant. The tiny fibers may then become airborne and irritate any part of the skin that isn’t covered up.

8. Spring Bulbs

Lily rash, tulip fingers, and hyacinth itch – all delightful terms to describe what can happen after working with spring bulbs.

These and other flower bulbs, including Narcissus species like daffodil and paperwhites, have the potential to inflame the hands, forearms, and the face with an itchy and burning sensation.

Hyacinth bulbs tend to be the worst of the bunch. Hyacinth itch affects the most people since the bulbs exude highly irritating oxalate crystals – the same toxin that makes rhubarb leaves poisonous.

Though rashes from spring bulbs usually amount to a minor annoyance and the symptoms resolve themselves quickly, repeated handling can worsen reactions over time. People most affected by it are those who work with bulbs regularly.

Even if you’ve never had a bad reaction before, sensitivity to spring bulbs can occur at any time. So before you go ahead and plant a field of bulbs in autumn for a dramatic show the following spring, put on your gloves first.

Tips for Protecting Yourself Against Irritating Plants

There are thousands of plants out there that will send out a toxic medley of chemicals as a warning to stay away. And we will all have different sensitivities and tolerances for these plant allergens.

When it’s not possible to avoid them, you’ll want to cover up. Wear pants and a long-sleeved top, footwear that fully covers your feet, and thick work gloves. When dealing with noxious weeds like giant hogweed, put on a face mask and eye protection too.

Plant toxins are generally at their highest in full sun. Avoid gardening between the hours of 10 a.m. and 2 p.m. as this is when the sun is at its strongest.

When you work in the garden, don’t touch your face or rub your eyes. Shower once the job is done and launder the clothes you wore in a separate load.

If your town’s garbage collection won’t take poisonous plants, don’t burn or compost them. The seeds will persist in the pile and spread through your gardens when you go to use the finished compost. Burning the plants has the potential to release the toxins into the air.

To dispose of them safely, bury the plant remains deeply in a spot that won’t be disturbed.

If your skin comes into contact with irritating plant sap, gently wash the affected area with soapy water. Use aloe vera gel to help soothe the rash and speed up the healing process.

Most of the time, the rash will clear up after a few days. If the wound develops red streaks or has lots of swelling, blisters, pus or discharge, you should seek medical treatment immediately.

Get the famous Rural Sprout newsletter delivered to your inbox.

Including Sunday musings from our editor, Tracey, as well as “What’s Up Wednesday” our roundup of what’s in season and new article updates and alerts.