In late spring, around the time the weather starts to be consistently nice – it happens. You’re outside, soaking up the sun, when you feel a tickle on your arm. Looking down, you see a tiny 2-3mm long, fuzzy black caterpillar inching (millimetering?) across your skin.

“Oh no,” you think, “they’re here.” Oh yes, the spongy moth infestation has begun.

You look ahead to the next few weeks with dread, knowing you’ll experience their full life cycle in your backyard – dozens of tiny fuzzy caterpillars covering everything in your lawn while they balloon, caterpillars dangling from trees to get caught in your hair, the sound of “rain” on the leaves that’s really just the sound of thousands of caterpillars high up in the trees pooping, caterpillar poop staining the roads, finding their sticky, tan egg masses all over your trees and patio furniture…

…and the defoliation and dead plants left behind when they finally die off for the year.

For those familiar with this pest (formerly known as the gypsy moth), their arrival kicks off a summer of annoying run-ins with this pest. Depending on how bad the infestation is and the weather, these hungry caterpillars can do serious damage, even leaving dead trees in their wake.

There are things you can do to slow their spread and mitigate damage, but you have to know at what point in the life cycle to take action. Learning about this common pest is the first step in controlling and slowing its spread across the country.

The Spongy Moth – Lymantria dispar

Many of us grew up using the common name, gypsy moth, but out of respect for the Roma people, it was renamed the spongy moth a few years ago – a nod to the spongy egg masses laid by the adult female.

Here in the States, Lymantria dispar is an invasive, nonnative species. The two types of spongy moth we deal with originally come from Europe and Asia, and like many introduced species, they have few natural predators here, so their spread has been significant.

You can now find both in almost half of the United States.

In the northeast, you will find the European variety of Lymantria dispar. The moth has spread quickly here and caused enough destruction that containing it has become a high priority. The European variant is found as far south as Virginia, as far west as Wisconsin and well into Canada, including Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island and Nova Scotia.

The Asian variety can be found on the west coast in states like Washington and Oregon. The spread of the Asian variety of spongy moth has been much easier to contain and presents less of an issue than the European moth.

Identifying the Spongy Moth Caterpillar

When they’re tiny, they’re easy to ID, mainly due to the time of year and where you find them – everywhere, crawling on everything.

However, once the spongy moth caterpillar is a little over a centimeter long, identification is easy due to the colored spots running in two rows down its back. If you look closely, you will see first two rows of blue dots and then two rows of red dots.

The adult moths are tan, with the male being smaller and darker. The females have a wingspan of about 5.5-6.5 centimeters, and the males 3-4 cm.

Interestingly, the females are flightless here in the States and Canada, despite being able to fly in their native regions.

The egg sacks are sticky, cream-colored masses of webbing, making them easy to spot on trees.

Spongy Moth Life-cycle

I think my colorful explanation of the spongy moth life cycle at the beginning of this article is pretty accurate. However, you may want something a bit more learned.

Hatching & Ballooning

Each sticky egg mass comes alive in late April or May with anywhere from 600-1,000 tiny, black caterpillars hatching. Yes, you read that right, per egg mass.

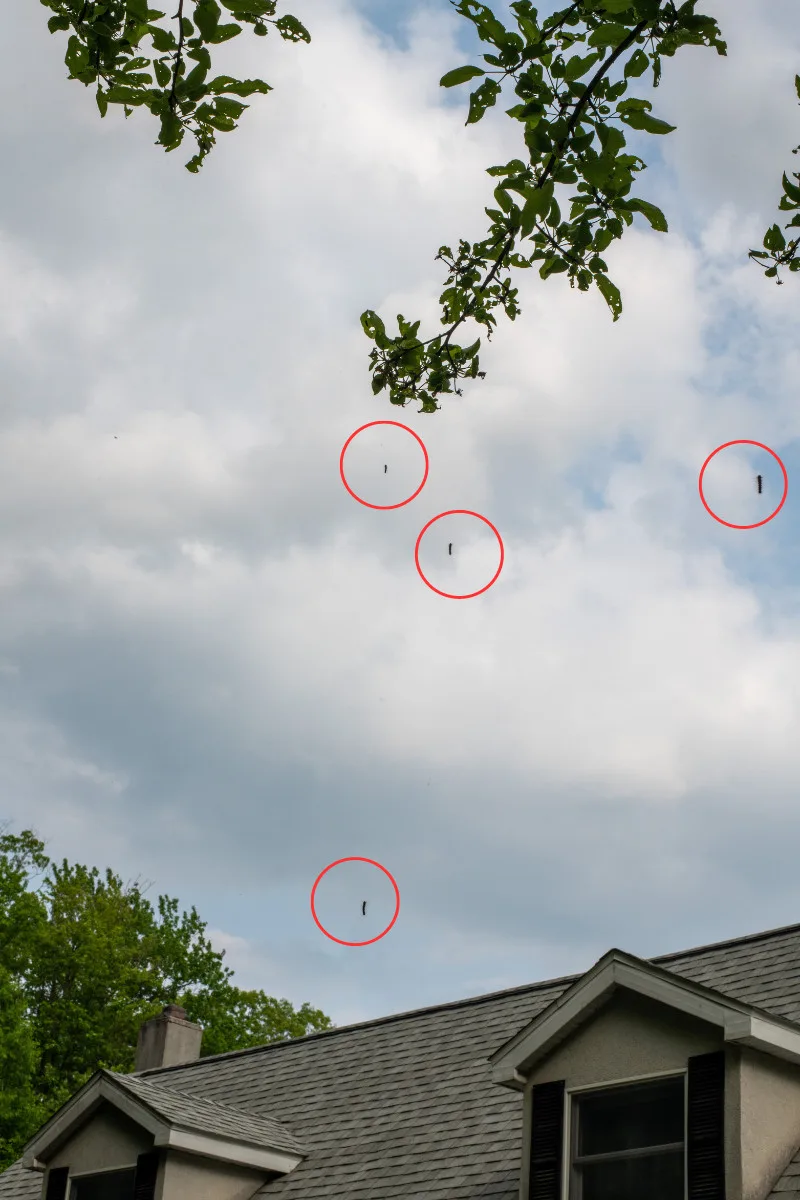

They make their way to the end of a branch or the edge of whatever manmade item the egg mass is attached to and disperse far and wide by “ballooning” – they dangle from a long silk strand until the wind catches them and carries them away.

Because they’re so small at this point and naturally fuzzy, the wind can easily carry them as far away as half a mile. Usually, they don’t spread further than 150 yards from their egg mass.

They will keep climbing, dangling, and ballooning until they land on something edible. Or in your hair, in which case they will meet a most violent end, as no one enjoys that nasty surprise.

Into All Lives a Little Poop Must Fall, or the Instar Stage

If you’ve ever read Eric Carle’s childhood classic, “The Very Hungry Caterpillar,” you know what happens next.

The caterpillar will continue to consume all the foliage in its path for six to eight weeks, growing through several instar stages (molting their skin as they grow) as they do. Around this time, you can stand quietly near the trees (I wouldn’t recommend under) and hear the soft pitter-patter of caterpillar poop hitting the leaves.

By the time they’ve completed their last instar, the males will be about two inches long and the females three inches. A drive through a wooded area with an active spongy moth infestation will show noticeable dark patches on the roads directly beneath large trees from all the caterpillar poo.

It’s Suddenly Quiet

At this point in the season, we get a short break of about two weeks as the caterpillars pupate in their burgundy cocoons.

When the adult moths emerge, we at least no longer have to worry about the foliage, as they don’t eat at this stage.

The larger female moth produces a pheromone which attracts the males. If you’ve ever watched a male spongy moth fly, you may have noticed their rather drunken back-and-forth flight pattern; this helps them pick up the scent.

The female will produce a single egg mass before dying a week after she’s pupated. Once mated, the male will continue to find other females to mate with before also dying a week after pupating.

And the Cycle Continues

The spongy egg masses, which can be as small as a dime or twice the size of a quarter, are easy to spot on bark because of their light, tan color. By the end of July or early August, you’ll have a pretty good idea of how bad next year’s infestation will be by how many egg sacks you see.

What Plants Do They Eat?

Unfortunately, the easier question to ask is what plants don’t they eat. The spongy moth nibbles on well over 300 plant species, with about half being excellent host plants to feed, hide and lay eggs on.

They prefer hardwood trees, oak being a prime target. Maple, birch, and alder are also preferred trees.

But you have to remember, just because those are the preferred trees doesn’t mean they won’t eat everything else in their path.

Can Spongy Moths Kill My Trees/Plants

The problem with these infestations is that they occur each year. A normally healthy tree can withstand being defoliated once or twice. New leaves will usually show up in midsummer. However, when you have infestations year after year, the tree is weakened, becoming less likely to bounce back and more susceptible to other pests and diseases.

When you add other factors such as drought, which is becoming more common, these annual infestations become a significant risk to your trees.

Spongy moth caterpillars can wreak havoc on smaller decorative shrubs and garden plants too.

If you live in a forested area or have many trees in your yard, the damage from a spongy moth infestation can be significant. Rarely do they limit their feeding to their preferred trees. For instance, they’ve made a mess of our beloved oak tree, but they’ve also found our apple tree and my rose bushes equally tasty, and I’m constantly picking them off of the plants in my garden.

How and When to Control Spongy Moth Infestations

While it’s unlikely we will ever eliminate the spongy moth, it’s important to slow their spread and contain them as much as possible. There are things you can do to protect your trees, shrubs and garden plants from damage each spring. But certain pest controls will only be effective during specific stages of the caterpillar’s life cycle.

You may need to adopt several forms of control for efficient pest coverage over the summer.

How We Help Spread this Invasive Species

While the female spongy moth prefers to lay her eggs on trees, she’s a terrible mother and will lay her eggs anywhere, which is why this species spreads so easily.

Anything remotely immobile that’s outdoors is fair game.

This means your outdoor furniture, grill, camping equipment, trailers, etc. If it’s outside and sits still long enough, it’s a prime spot for a spongy moth egg sack. This also includes cars and vehicles.

When we move to a new area or go camping, we’re likely bringing an egg sack or two along with us. Shipping goods across the country can spread the moths too.

Do the Caterpillars Bite?

While the spongy moth caterpillar can’t bite, the fuzzy hairs can cause a rash or irritated skin. It’s recommended that you wear gloves when dealing with them.

Burlap Bands & Sticky Tape

During the hottest parts of the day, caterpillars will come down out of the leaf canopy to escape the heat. They will hide in the grass and cooler cracks and crevices of the bark until things cool off. Using burlap wraps around tree trunks, with a belt of sticky tape placed further down the trunk, you can capture and dispose of lots of spongy moths while they’re at their most destructive.

Start setting up burlap traps as soon as you see caterpillars emerge, and check and change the sticky tape as needed.

Even if you don’t use sticky tape, wrapping burlap around your tree and then going out to squash or drown your finds in the afternoon is also effective.

Pheromone Traps

When the munching stops and things go quiet, that’s the time to employ pheromone traps. Remember, the female moth emits pheromones to attract the male. You can use pheromone traps with sticky tape to attract and collect male moths, preventing them from finding a mate.

Naturally, this type of trap only works on adult male moths, but used in conjunction with burlap traps or biological treatments, it’s quite effective in disrupting next year’s infestation.

Destroying Egg Sacks

This might seem like a thankless task if it’s one of those years where you find them everywhere. Scraping egg masses off of trees and other places you find them is one of the best ways to prevent next year’s infestation and keep them from spreading.

I’ve found that a pocket knife works well to scrape them off of trees gently. Place the egg mass in a bucket of soapy water with a lid to kill the eggs.

Of course, this only applies to the ones low enough on the trees for you to reach. You may want to contact a local tree care or landscaping center to see what spraying options you have to protect your trees. Many offer chemical-free options these days, relying on biological controls such as bacteria and fungi.

One thing we can do to help stop the spread of the spongy moth is to look over vehicles, outdoor furniture, and accessories each fall and remove egg sacks. If you’re camping, don’t bring your own wood; check campers and other camping gear for egg sacks before heading out.

Biological Controls

Because of the damage they cause and the need to stop their spread, there is ongoing research on using fungi and bacteria for the biological control of spongy moths. While there have been some important findings, many of the most effective options are difficult to mass produce, so they aren’t readily available to consumers yet.

Bacillus thuringiensis

Bacillus thuringiensis is a naturally occurring bacteria that only affects insects; it’s harmless to us and other animals. When the spongy month eats leaves sprayed with Bt, the bacteria make protein crystals that disrupt the insect’s digestive system, causing it to die before it can reproduce.

Unfortunately, Bt affects all caterpillars in an area, so native species are also killed, making spraying programs merely a trade-off rather than a perfect solution.

Bt is also an option for the home gardener, whether from a bottle or through a spray program offered by a local tree care provider.

Trichogramma wasps

These teeny-tiny parasitic wasps lay their eggs inside the developing eggs of spongy moth caterpillars. Instead of a spongy moth caterpillar hatching from the egg, an adult trichogramma wasp will emerge.

And what does the adult trichogramma eat? Pollen and nectar. Yup, you would be adding a tiny army of pollinators to your yard. Not too shabby.

The best part is they work equally well on cabbageworms, tomato hornworms, corn earworms, cutworms, armyworms, and imported cabbage worms.

You can purchase trichogramma eggs that come “glued” to cards you hang in your trees to release.

Spraying Programs in the United States & Canada

In areas of the northeastern United States and Canada, where spongy moth populations are heaviest, many states, provinces and municipalities have adopted spraying programs. In an effort to slow the spread of this invasive pest and to protect forested areas, Bacillus thuringiensis is sprayed early in the season, just before the eggs begin to hatch.

My sweetie lives right on the edge of stage game lands. We watched in late April as a crop duster pilot sprayed the forest with bt. It certainly didn’t help our trees.

Some municipalities may even offer discounted spraying if you sign up to have your yard sprayed while other forested areas are treated. The best place to start for spraying information in your area is through your county extension office.

Spongy moth infestations tend to be cyclical, lasting five to ten years.

They get worse each subsequent year until suddenly the population drops off, usually from a naturally occurring virus that shows up in very large populations of the moths (Nucleopolyhedrosis virus), which causes an entire population to crash. And then the cycle starts over again.

No matter how bad spongy moths are each year, you can save your foliage and some headaches by helping to stop their spread.

Get the famous Rural Sprout newsletter delivered to your inbox.

Including Sunday musings from our editor, Tracey, as well as “What’s Up Wednesday” our roundup of what’s in season and new article updates and alerts.