I know this article is going to catch a lot of heat because GMOs are a hot-button topic among gardeners. But the amount of fear-mongering over non-GMO seeds is baffling to me. Mainly because, as a home gardener, you aren’t going to run into them. Yes, you read that right. Before you whip out the paper mâché to create an effigy of me and set it on fire, I’m going to ask you to read the article, please, not just the headline.

An important note – I’m not here to argue in favor of or against GMOs.

The point of this article is to clear up the mystery surrounding non-GMO seeds. I’ll leave it to you to form your own opinions about bioengineering and food.

For years now, I’ve been baffled by the amount of fear over non-GMO seeds among gardeners.

You can’t find a gardening forum or wade through the comments section of a gardening Facebook page without bumping into scads of warnings about genetically modified seeds. “Make sure you’re only buying non-GMO seeds!” “Has that seed company signed the ‘Safe Seed Pledge’?” “Look for the non-GMO label on the seed packet.” And on it goes, confusing new and old gardeners alike.

At the end of the day, as a home gardener, you can’t buy genetically modified seeds.

What’s the Difference?

If we’re going to clear up the confusion around non-GMO seeds, then it’s best to start with a seed primer. Many gardeners, new and old alike, are confused about the terminology surrounding seeds and, especially, the terms to describe bioengineered food. Hybrid, heirloom, organic, non-GMO, genetically engineered, transgenic — what do they all mean?

Heirloom

Heirloom seeds are open-pollinated (meaning they need to be pollinated by wind, rain, pollinators, or by hand) varieties that have been saved and grown again for generations. Some varieties are hundreds of years old. Some are specific to a certain region. These seeds breed true year after year with little variation as long as they don’t cross-pollinate with another variety of that species in your garden.

For example, say you’re growing two different varieties of heirloom squash in your garden. They will naturally cross-pollinate. If you save those seeds, you’ve got yourself a surprise hybrid for next year with traits from both of the parent plants. (This can actually be a lot of fun. Squash gets really weird when cross-pollinated.) Some veggies cross-pollinate much easier than others.

Heirlooms tend to be more disease-prone. You can struggle to grow them successfully if you choose an heirloom variety from a region that’s vastly different from your own. For instance, an heirloom bean from Florida might not do as well if you grow it in Minnesota.

The sheer variety of heirloom seeds is what makes them fun to grow. All the best tomatoes are heirlooms, in my opinion. Not to mention, we’re still discovering new cultivars all the time, which is a good thing because we’re losing so many, too.

Hybrids

Hybrids are not GMOs. They’re simply the product of selective breeding. Plants are chosen for a specific trait and cross-pollinated with another plant with a different desirable trait to create a generation of plants (via the seeds) that have both traits in them.

Common desirable traits are size, flavor, and tolerance to disease or drought. The seeds are saved from the cross, and voila, you have a giant, flavorful, blight-resistant, drought-tolerant tomato hybrid.

You’ll often see the designation ‘f1’ or ‘f2’ next to hybrid vegetables.

Alas, this doesn’t mean they are Formula One racing sponsors. These denote the first or second filial generations, meaning the hybrid came about by crossing two non-hybrid parent plants to get a new hybrid (f1) or by crossing two hybrid plants to get further desirable traits in the second generation of hybridization (f2).

One thing you’ll see noted about hybrids is they generally don’t breed true in subsequent generations.

So, if you want to grow the same plant you did this year, you’ll need to plant the same hybrid seeds. However, it’s still fun to save seeds from hybrid plants just to see what you get in subsequent years.

Heirlooms vs. Hybrids

An elitist attitude has popped up around heirlooms, and I don’t get it. I often wonder if folks are confusing hybrids with GMOs. (Again, hybrids are not GMOs.) There’s nothing wrong with growing either type of seed in your garden, and most of us end up growing both heirlooms and hybrids. In fact, I hate to break it to you, but that heirloom started its life as a hybrid at one point.

Humankind has been cultivating new varieties of plants ever since we learned how to farm. If we hadn’t embraced breeding plants we’d all still be eating tomatoes the size of peas that are more sour than sweet.

Organic Seeds

Hybrid seeds can be organic, and not all heirloom seeds are organic. When it comes to seed production, all that organic means is that the plant grown for seed was grown with organic methods that met a certain standard. To that end, GMOs cannot be organic.

Genetically Modified Organisms

A genetically modified organism is one whose genetic makeup has been altered by genetic engineering (bioengineering). (How many times can I say genetic in a sentence?) This can be something like editing the genome or adding genes from a different species altogether.

Transgenic Organisms

A transgenic organism, plants in this case, is one that has been altered to include genes or DNA from a different species entirely. Whereas a GMO means the organism has had its own genetic material changed (usually, something is removed from the DNA strand).

Okay, now that we’ve cleared that up, let’s talk about why you don’t need to worry about GMOs showing up in your garden.

GMOs Are Highly Regulated

I’m going to make this short and sweet. Since 2016, the USDA has been required to put out an annual report of all bioengineered food throughout the world, whether or not these crops are sold or grown in the US or not. You can check it out here.

Currently, this list includes 13 commercial crops and a bioengineered salmon.

(I’m not overly worried about non-GMO salmon seeds showing up in my Johnny’s catalog.)

These thirteen crops are commercially grown. The seed is not available to you and me, and the biotech companies behind them want it that way.

Is Your Signed Technology Stewardship Agreement on File?

If you want further proof that GMO seeds are not available to the public, ask yourself this question. The last time you purchased seeds, be it online, from a catalog or in a store, did you first have to prove that you had a signed technology stewardship agreement on file?

No?

Then, you are in no danger of accidentally buying GM seeds for your garden.

Beyond being highly regulated by the government, GMO technology is big business. Everyone knows the big one – Monsanto, which doesn’t exist anymore. Bayer bought them in 2018 for $63 billion. See? Big business.

Millions, if not billions, of dollars are spent on the development of these crops. The IP behind them is patented and protected to the nth degree. Growers have to sign a contract known as a technology stewardship agreement.

These agreements are there to protect the technology behind the seeds and to keep the corporations in compliance with federal regulations. They are not there to protect the farmers growing them, but that’s an article for another day.

Here are a few things you’ll have to agree to when you sign a Bayer TSA:

- To use seed only for a single planting of a commercial crop in the United States

- Not to give, sell or export the GMO seed to anyone else

- Not to save seeds from the GMO crop for planting again next year

- You agree to allow representatives from Bayer to inspect the land where you’re growing the crop at any time

- You waive the right to bring a class action lawsuit against Bayer

What you get when you sign this contract is a license that allows you to buy and grow their seed strictly according to their rules.

Needless to say, you aren’t going to find these kinds of seeds between the pages of the Whole Seed Catalog or in the Burpee packets at Walmart.

Why Aren’t We Mad at the Seed Companies?

Back in the early 2000s, when this whole GMO seed scare started, everyone liked to point their finger at Monsanto as the big, evil corporation behind most GMOs. Don’t get me wrong, I liked to hate on Monsanto like everyone else. (Hello, Soda Springs Superfund Site!) But they weren’t even selling genetically modified seed to home gardeners. No one was.

The fact is, your favorite seed company is just as much to blame.

The same seed companies who like to play up how wholesome and good they are with their selection of organic and heirloom non-GMO seeds also helped fan the flames of fear around GMOs showing up in our gardens.

None of them bothered to point out to consumers that:

- There were no GMOs beyond commercial crops.

- GMOs are highly regulated by the government.

- The few available crops are only available to commercial growers with a license.

These seed companies had the opportunity to stop the spread of misinformation in its tracks, and they chose not to.

Instead, most adopted a non-GMO label on their packaging or touted that they had signed the “Safe Seed Pledge.” Their actions implied that GMO seeds were floating around somewhere in the home gardening world. But not in their seeds! So, you’d better purchase your seeds from them because they have the little non-GMO label, and they signed a pledge.

I treat the non-GMO label on seed packets like that green ‘organic’ label on a box of processed mac and cheese or a ‘gluten-free’ label on a gallon of cow’s milk – it’s about as useful as a screen door on a submarine.

If You’re Concerned About GMOs, Look in Your Closet, Your Gas Tank and in…Nature

If you’re concerned about GMOs, then you probably know the biggest problem is at the grocery store.

Pretty much anything with soy or corn in it is a bioengeineered food. Thankfully, food that contains GMOs has to be labeled as such now.

You’re better off growing more produce yourself if you want to avoid GMOs.

GMOs are in more than just our food supply. They’re in the clothes we wear in the form of GM cotton. They’re in our gas tanks in the form of GM corn (ethanol). It would appear that GMOs are here to stay.

But the interesting thing is nature has been messing with genes and DNA in plants much longer than we have and at a much more impressive rate.

Take holly, for example. If an animal nibbles on a holly plant, the plant will alter the DNA in the leaves growing lower on the tree to grow spikier. That’s scarily fast gene adaptation.

In the past few years, we’ve even discovered a large number of naturally occurring transgenic plants.

Let that sink in for a minute.

There are plants.

In the wild.

That have DNA from a completely different species.

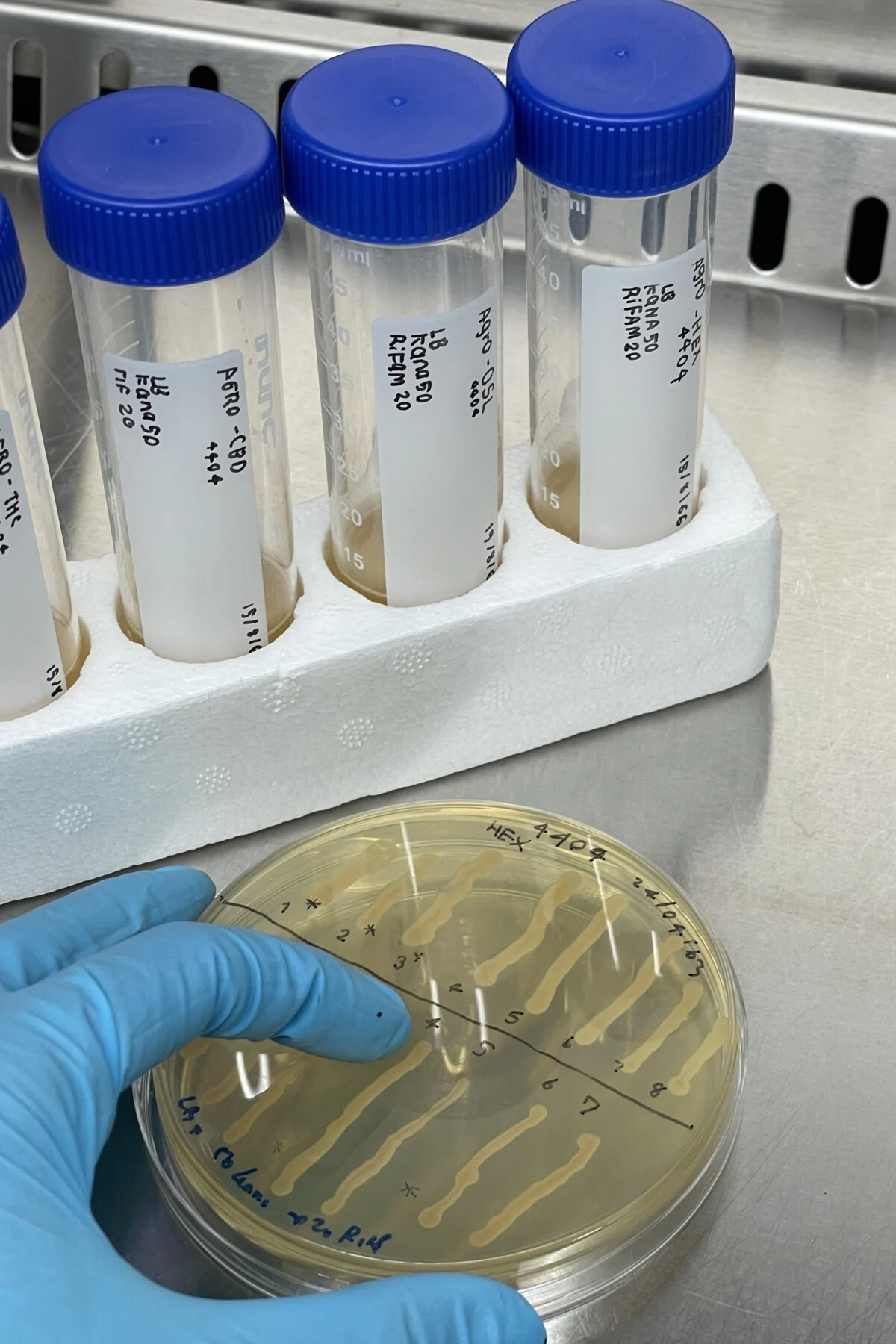

Agrobacterium.

Scientists have found that genes from this naturally occurring bacteria have made their way into the genes of about 1 in every 20 flowering plants they tested (roughly 625 different species). This suggests that not only are humans late to the GMO game but that GMs in nature are probably a heck of a lot more common than we know.

Even more interesting is that this gene-that-doesn’t-belong was found in quite a few foods we eat regularly, such as sweet potatoes, peanuts, tea plants and bananas. So, for those of you who are avoiding GMOs, you’ll have to add those foods to your list because, apparently, nature flooded the market already.

After all is said and done, I guess there is one GMO you might be growing in your garden without knowing it – the sweet potato. But you’ll have to blame Mother Nature rather than Bayer this time.

Get the famous Rural Sprout newsletter delivered to your inbox.

Including Sunday musings from our editor, Tracey, as well as “What’s Up Wednesday” our roundup of what’s in season and new article updates and alerts.