Fittonia (also known as the nerve plant) is one of those houseplants that is both a looker and easy to find for sale (not a small feat in the world of Instagram #rareplants trend).

I had my first fittonia plant for almost four years before I had to give it away when I was moving long-distance. You’d better believe that one of the first five plants I re-bought in my new home was another fittonia.

There’s something innately rebellious about having a houseplant that’s not the classic green color plants are “supposed” to be. Although I wouldn’t call nerve plants low maintenance, I also wouldn’t throw them in the same category as the fussy fiddle leaf fig or banana plants. Keep those primadonnas away from me, please!

Over the years, and after some near misses, fittonia and I learned to love each other. And what started as one trial houseplant turned into a small collection of colorful-foliage companions.

If you also fell under the spell of a nerve plant, here are some tips on how to take care of this cheerful houseplant.

Why is fittonia called a nerve plant?

The Latin name of the nerve plant is Fittonia albivenis, where “albivenis” literally means “white veins”. So it’s the distinctive veins that run along the leaf surface that earned fittonia the “nerve plant” nickname.

The name of the genus – Fittonia – is a tribute to Irish botanists Sarah and Elizabeth Fitton who wrote numerous studies on plants starting in the 1820s.

By the way, can you guess what purpose the lighter veins serve in a fittonia? I didn’t know until recently, when I read about it in The Kew Gardener’s Guide to Growing House Plants by Kay Maguire. (This is a book I highly recommend to all houseplant enthusiasts.)

In the wild, fittonia can be found growing in the rainforests of Latin America in Peru, Ecuador, Brazil, Bolivia and Colombia. Because it’s an undergrowth with a creeping habit, fittonia has adapted to the low light levels by developing these white veins to help attract and trap as much light as possible.

You’ll notice that the veins are not always white, but they are always lighter in color than the rest of the leaf surface.

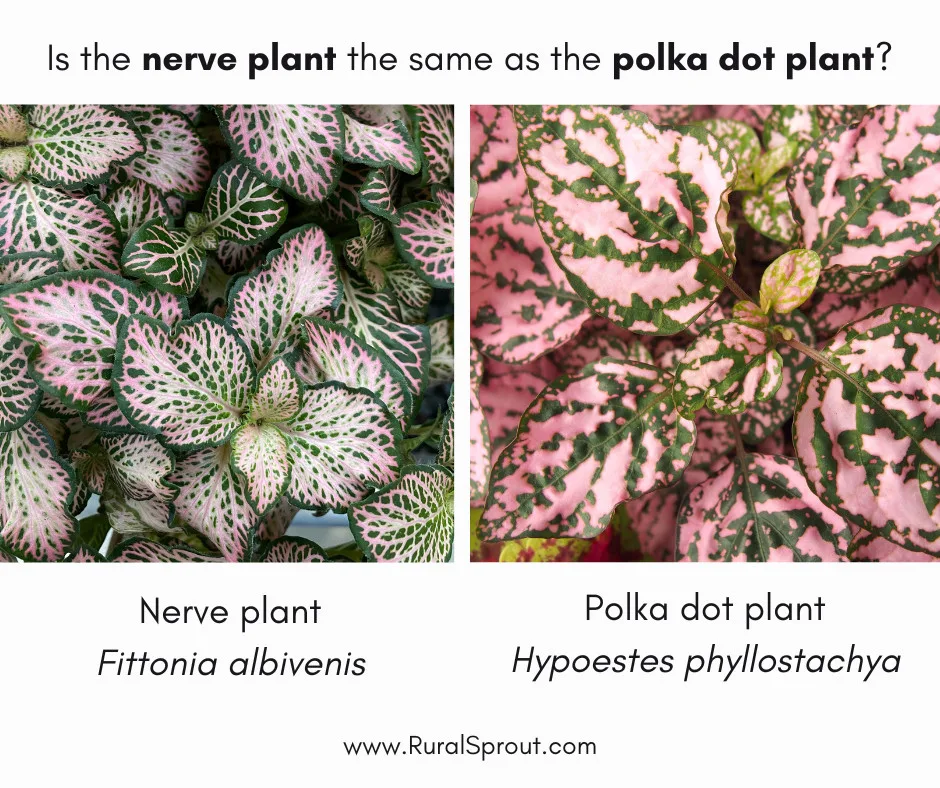

Is fittonia the same as the polka dot plant?

No, they’re not the same plant, although they both belong to the same family, Acanthaceae.

The freckled polka dot plant is a Hypoestes phyllostachya. It has also been growing in popularity recently, and it has a lot of visual elements in common with the nerve plant. They may come in the same colors and usually grow to about the same size. To make matters even more confusing, some hypoestes cultivars have a leaf pattern that more closely resembles veins rather than usual polka dots.

Here’s a closeup of two plants. Can you guess which one is a nerve plant and which one is a polka dot plant?

Is fittonia hard to care for?

In my experience, it isn’t hard to keep a nerve plant alive and happy. But I wouldn’t put it on a list of houseplants that thrive on neglect, either. One thing I would call fittonia is intuitive. It will tell you what it needs and when it needs it and take the guesswork out of plant care.

Does fittonia need a lot of light?

This sounds like Chapter One of the “How to read fittonia like a book” guide.

Remember that the nerve plant is, at its core, a tropical undergrowth. So it does well in low to moderate light that falls at an indirect angle. If it’s not getting enough light, the nerve plant will start stretching toward the sun. Luckily, it won’t get as leggy as a sun-deprived succulent, but you will be able to tell.

On the other hand, if your fittonia gets too much bright direct light, it will let you know by turning brown and crispy. You can solve this by moving it away from the source of direct light. If a sunny windowsill is all you’ve got available, you can protect your plant by placing it behind a sheer curtain.

The nerve plant cannot handle strong sun, so this is also one of the reasons why it’s not a good idea to move it outdoors in the summer.

Where should I place my fittonia?

In addition to light requirements, you should also pay attention to humidity levels and drafts when you find the perfect spot for your fittonia.

The nerve plant prefers a level of indoor humidity above 60 percent (higher, if possible and safe in your home). You can increase the humidity around your fittonia by either grouping it with other houseplants or placing it on a pebble tray full of water. (I explained how I make my humidity tray in this post.)

Don’t place it in front of or next to sources of heat, such as fireplaces, floor vents or radiators. While it does like a bit of warmth, it will not do well in temperatures that go above mid-80s F (about 30C).

How often should I water my fittonia?

Fittonia likes moisture, both in the air and in the soil. But like most potted houseplants, you shouldn’t let it linger in a puddle of water.

My usual advice for houseplants is to water them when the top couple of inches feel dry to the touch. (By the way, you can use a stick probe if you don’t want to get your fingers dirty testing the soil.)

But I found that this piece of advice doesn’t often apply to fittonia. By the time the soil gets this dry, the plant has already started its “fainting” act. You’ll recognize it when you see it. The leaves lose their hydration, flop down and start curling inwards. This is another way that the nerve plant communicates its dissatisfaction.

I don’t wait for this to happen before I water my nerve plant. I admit that I used to wait, until one particularly busy week when I procrastinated a bit too long.

So I ended up accidentally killing part of a fittonia plant. I suspect there were two plant plugs potted up together, and one of them just couldn’t handle the drought stress.

I now water the fittonia when the soil barely starts to dry out.

Does fittonia flower?

Yes, fittonia does produce flowers. But don’t hold your breath for stunning blooms. I’d go as far as saying that fittonia flowers are rather underwhelming, compared to this houseplant’s foliage. The flowers last for months, but they rarely open up fully in an indoor environment.

In fact, some growers prefer to pinch the flowers so that the plant directs its energy into growing more leaves. In my opinion, that doesn’t make much difference unless you’re planning on cutting and propagating that specific stem.

How do I propagate my fittonia?

Speaking of, there are two easy ways to propagate fittonia. In my experience, both of them work well, although the first one has been more reliable than the second one for me.

1. Propagation by stem cuttings.

Let’s start with the foolproof method. The easiest way to make more nerve plants is by taking stem cuttings, just as you would for any other houseplant. Simply cut a bit of the stem that has at least one set of leaf nodes, remove the leaves and pluck it in water. You’ll start seeing roots forming in a couple of weeks.

But it’s better to wait for a sturdier root structure before you transplant it into soil. It may take six weeks or even two months for the new plantlet to be ready for its new home.

The nerve plant has shallow roots, so don’t bury them too deeply. You can even get away with using a shallow pot (like the ones you would use for bulbs) for a young plant.

2. Propagation by root division.

This also worked well for me, but I didn’t have a one hundred percent success rate.

Start by gently lifting the plant by the stem and digging out the roots. Remove as much of the soil from the roots until you can see the root structure clearly. Then separate the root ball into two or three sections.

Repot each section in its own individual container with drainage holes. Fittonia prefers potting soil mixed with materials that improve drainage, such as bark, coco coir or perlite. Keep the newly potted plants moist (but not soggy) until you start seeing new growth.

I confess that, even though this is the quickest propagation method for fittonia, it didn’t always work for me. One time, I divided a larger plant into three smaller ones (ka-ching!), but only one of the three survived. After about three weeks from division, the other two plants took turns in dying a very crunchy death.

I suspect that I either didn’t take enough of the root structure to sustain new growth or didn’t keep the new plants hydrated enough. It could have been both reasons.

I can also tell you what doesn’t work, based on my personal experience: starting fittonia from seed. If you’ve ever had the “brilliant” idea to start your nerve plant from seed just to get more plants for less cash, save yourself the trouble. Fittonia seeds are very small, very finicky and very unlikely to have been pollinated by whoever is selling them.

Does fittonia grow large?

Nope, fittonia is a very slow grower, which makes it the perfect plant for small spaces. You can plop it on your desk at work or place it in a nook that needs cheering up at home. Its pink, red, maroon or peachy leaves will quickly brighten up any spot.

Depending on the cultivar, fittonia will reach between 3 and 7 inches in height (7-17 cm).

There is a bigger species of fittonia in the genus, called Fittonia gigantea. Although I’ve only ever seen this one grown as undergrowth in greenhouses in botanical gardens. What you’re most likely to find for sale is different varieties of Fittonia albivenis.

If a small fittonia is what you’re after, look for the word ‘mini’ in the name of the cultivar. For example, Costa Farms offers ‘Mini Superba’, ‘Mini White’ and ‘Mini Red Vein’ as options.

There’s a fittonia for everyone out there, and keeping this plant happy and thriving is not as hard as you might have thought.

Get the famous Rural Sprout newsletter delivered to your inbox.

Including Sunday musings from our editor, Tracey, as well as “What’s Up Wednesday” our roundup of what’s in season and new article updates and alerts.