If you have a backyard flock, two words can make your heart skip a beat – avian influenza.

HPAI has been splashed all over the news for quite some time, accompanied by statistics quoting the number of birds lost at commercial farms or dollar amounts in lost revenue. But what does this disease mean for the backyard chicken owner?

The Importance of Being Informed

With the uptick in cases in the United States and abroad, we at Rural Sprout feel it’s important for readers to have information related to small flock owners. Most information is geared toward large farms and commercial setups. While much of it is useful, it can be difficult or unnecessary for the backyard flock owner to adopt some of the practices they recommend. Our goal isn’t to be sensational or to shock you but rather to equip you with information about the risk to your flock, so you can take precautions to protect them.

I contacted Dr. John Boney, Assistant Professor of Poultry Science at Penn State University, to discuss the risks to backyard poultry owners and what measures they can take to protect their birds. He’s working with the Penn State Extension to bring awareness of this potential threat to farmers all over Pennsylvania.

Luckily, it’s easier to manage the risk to a backyard flock because of its size. We will look at the disease, how it spreads, its symptoms and what to do if you think you have an infected bird.

What is Avian Influenza?

Avian influenza is a highly infectious virus that occurs naturally in wild migratory waterfowl worldwide. From Dr. Boney,

“This particular strain of highly pathogenic avian influenza is of Eurasian lineage. This virus is being transmitted from continent to continent through migrating waterfowl. This presents a tremendous challenge to poultry producers around the world.”

Why is Avian Influenza so Dangerous?

Avian influenza is a big problem for three reasons:

- It’s incredibly infectious, with the possibility of wiping out an entire flock

- Birds carrying the virus can show no symptoms

- The disease moves quickly, with the major “symptom” being sudden and unexplained mortality

Chickens, turkeys and domestic ducks are all susceptible, so you can imagine the panic in the commercial poultry industry. It’s no less worrying for those of us with birds we consider pets.

How Does it Spread?

Migratory waterfowl are the natural carriers of avian influenza. This includes gulls, terns, herons, cranes and other shorebirds, also wild waterfowl such as ducks, geese, and swans. The virus spreads through contact with saliva, mucous, and feces, which can also be present on feathers and dander. Transmission usually occurs through contact with a sick bird, or from contact with infected feces, feathers, etc., in an area where waterfowl are present.

How to Protect Your Backyard Flock?

Dr. Boney suggested that for the backyard flock, it may not be practical to implement many of the biosecurity measures that are in place at large farms or commercial facilities. But he maintains that good biosecurity is the best way to protect your birds.

Biosecurity Measures for the Backyard Flock Owner

- Always be mindful of where you’ve been before entering your chicken coop or handling your birds. If you’ve visited a park with waterfowl or somewhere with another flock present, change clothes before entering your chicken coop or handling your birds.

- Always wash your hands before and after caring for your flock.

- Have a designated pair of shoes or boots you only use when caring for your chickens. Do not wear them anywhere else.

- If you have friends or family visiting who also have chickens, do not let them handle your birds.

The Biggest Risk Factor for Backyard Flocks

During our conversation, Dr. Boney said that in most cases, when a backyard flock contracted the disease, there was a water feature nearby that attracted migratory waterfowl such as streams, rivers, or ponds. It’s not only direct contact that you need to worry about. The disease can be transmitted through feces and feathers lying on the ground. Infected waterfowl passing overhead can present a risk as feathers and dander are shed in flight.

Dr. Boney suggested keeping your flock contained and not letting them free-range if you have waterfowl present in bodies of water near you. During peak avian flu season (during migration, October through February) or in areas where the virus has been reported, it’s best to keep the birds inside their coop to prevent infection.

Purchasing Chicks or Other Birds to Add to Your Current Flock

If you’re purchasing birds, it’s always best to look for an NPIP-certified hatchery. The National Poultry Improvement Plan is a voluntary program that both commercial poultry facilities and hobbyist poultry keepers can join. Members work with state officials to certify that their flocks are free of specific diseases.

There are plenty of swaps advertised in local Facebook poultry groups and birds available on Craigslist. For many of us, this is an easy way to add new breeds to our flock without having to meet a minimum bird purchase. However, this comes with the risk of exposing your current flock to disease.

Dr. Boney advises you to quarantine new birds for 2-3 weeks where they won’t have contact with your flock. Always attend to your established flock first and wash your hands well before tending to the new birds. This way, if the new birds carry something infectious, you’re less likely to transmit it to your flock.

What to Look For

As we mentioned, the reason this disease is such a problem is that birds carrying it might not have any visible symptoms. Often the first “symptom” is the sudden death of a bird. Chickens are masters at hiding sickness to prevent henpecking, which makes watching for symptoms even harder. If you live in an area where avian influenza has been reported, reach out to your local extension office for more specific advice on how you can protect your flock.

Symptoms of Avian Influenza Include:

- A sudden loss of a bird or birds, often without any sign of illness

- Not eating or drinking

- Lethargy or a lack of energy

- A decrease in egg laying

- Soft-shelled, thin-shelled, or misshapen eggs

- Swelling or purple discoloration (similar to the color of a bruise) of the comb, eyelids, or legs

- Difficulty breathing

- Coughing, sneezing, and/or nasal discharge

- Difficulty walking, stumbling

- Holding the head or twisting the neck in an odd position

- Diarrhea

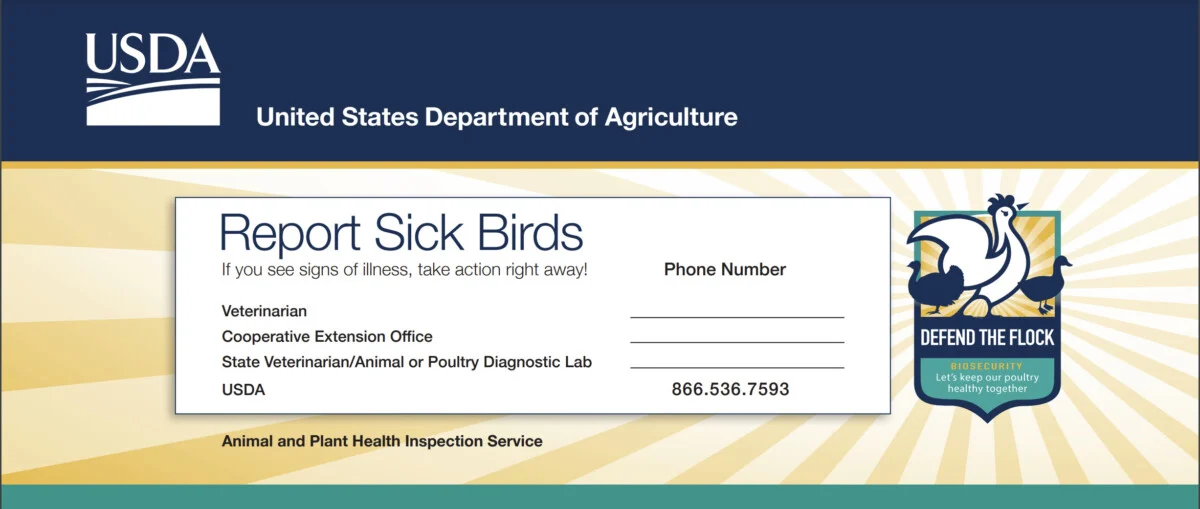

What Should I Do If I Think I Have a Sick Bird?

Isolate the bird from the rest of your flock, and wear gloves and a mask if you have them available. Be sure you wash your hands thoroughly and change your clothes after handling the bird. You want to minimize the risk of spreading the disease in your flock.

Call the USDA sick bird hotline – a quick Google search for “USDA sick bird hotline” will also pop up your state’s hotline in the results.

You will be connected with a vet who will triage your call and decide what steps to take. This may include having a vet come out to test your flock (with a swab) for HPAI.

Are Other Pets or Humans at Risk?

While it has happened that some mammals and humans have contracted avian influenza, it’s rare. Before you freak out too much, let me repeat that – it’s rare. There has been one human infection in the States from this recent outbreak. (CDC Avian Flu Summary)

Pets known to eat poultry are the ones more prone to becoming infected. Take this into consideration when letting dogs or cats outside near bodies of water with waterfowl; that includes walking them in public parks that have migratory waterfowl present. Hunters who use dogs to retrieve waterfowl should be aware of the risk.

Again, transmission to pets is not a common occurrence, but the possibility does exist.

The risk is less that your pet would become infected, and more that they could carry infected feces, feathers, or dander back to your birds at home.

You can read more about pet transmission at the CDC.

Human infection from a bird is even less likely than your pets getting it. But again, the possibility exists. It usually happens when a person has a long or repeated exposure to an infected bird. The CDC keeps close tabs on human transmission.

“…because of the possibility that bird flu viruses could change and gain the ability to spread easily between people, monitoring for human infection and person-to-person spread is extremely important for public health.”

Again, head over to the CDC to read more about it.

Our Responsibility as Backyard Flock Owners

Backyard flocks have exploded in popularity over the past couple of decades. But this growth hasn’t been easy, especially for urban chicken owners. People have worked hard to convince town and city councils all over the United States to change outdated laws, allowing more and more people to keep chickens in their backyards.

For most of us, our birds are pets. We enjoy their goofy personalities and grow quite attached to these lovable chickens. It’s up to you to decide how to use this information to protect your flock and evaluate the risk for you, your birds and where you live. As backyard chicken owners, we are responsible for protecting our flocks and reporting suspected cases. In doing so, we’re protecting everyone’s flocks.

Get the famous Rural Sprout newsletter delivered to your inbox.

Including Sunday musings from our editor, Tracey, as well as “What’s Up Wednesday” our roundup of what’s in season and new article updates and alerts.