Attracting ladybugs to your garden is one way to maintain diversity and manage it organically. Organic gardening always involves recognizing that we are not alone in our gardens. Successful gardens are diverse ecosystems that teem with life.

And all of that life has its role to play in helping the system to thrive.

Ladybugs are one creature that can help us, but what exactly are they? What do they do in our gardens? How can we attract them? Should we introduce them? And when we have them in our gardens, how can we encourage them to stay? Read on to find out.

What are Ladybugs?

Ladybugs, also called ladybirds, ladybird beetles, or lady beetles, are a range of small insects in the Coccinellidae family. Most members of this family are considered to be beneficial to your garden. However, there are some sub-family members that can cause problems for crops.

Identifying different ladybugs can be important. It can allow you to determine whether you’re looking at species native to your area or ones that have been introduced or are invasive.

It’s important to understand which ladybugs should be encouraged in your garden and which may pose more of a problem.

While ladybugs in the garden are generally a good thing, identifying different species can help you understand the ecology of the area and do your part to encourage good balance in the ecosystems.

How the Ladybug Got Its Name

Many people think of the ladybug as a red-colored creature with black spots. (A creature that often features in children’s books and children’s tales.)

The name Coccinellidae comes from the Latin word ‘coccineus’, which means ‘scarlet’. This led to an association with Mary (Our Lady) in the Christian world. (She was often depicted wearing a red cloak in early paintings.). Hence the ‘Lady’ in the name.

But ladybugs actually come in a wide range of colors. Often, they are red, orange or yellow, with small, black spots. But some have whitish spots on a brown background, some have stripes, and some are entirely black, brown or gray and have no spots at all.

It’s not always easy to recognize all the members of this family as being part of this family at all. However, the most common members of the ladybug family are easily identified.

The Benefits of Ladybugs in the Garden

Many ladybugs are hugely beneficial in your garden because they are a predatory species that eat common sap-sucking insect pests such as aphids and scale insects. They’re also the natural predators of a range of other pest species.

For example, Stethorus black ladybugs can pray on mites, like Tetranychus spider mites. They are also predators of the European corn borer (a moth that causes important crop losses in the US each year).

Larger ladybugs attack caterpillars and beetle larvae of various types. Some feed on insects or their eggs.

Different types of ladybugs have different favored prey. But almost all can help control pests and maintain a balance in your garden ecosystem.

Ladybugs also have other secondary food sources, such as nectar, and some also feed on mildew. As ladybugs come to eat from flowers, they also carry pollen from one flowering bloom to another. Unlike bees, ladybugs are not primarily looking for nectar, they will eat some, and pollination is a side effect as they go about their business.

In their turn, ladybugs are also a good source of food for other beneficial creatures in your garden. The main predator of ladybugs is usually birds. But frogs, wasps, spiders and dragonflies may also make a meal of these insects.

Are All Ladybugs Good For Gardens?

While ladybugs are generally a boon for gardens, it’s important to remember there are certain ladybugs that will not be as beneficial.

The Mexican bean beetle, for example, is part of the ladybug family but is a common and destructive agricultural pest.

Some others may be partly welcome – but partly harmful.

For example, the Harmonia axyridis (the Harlequin ladybird) is now the most common species in the US. But this is an introduced species. It was introduced from Asia to North America in 1916 to control aphids. This type of ladybug now outcompetes native species.

It has since spread through much of Western Europe and reached the UK in 2004. This species has also spread to parts of Africa. In some regions, it has become a pest and gives cause for some ecological concern.

Coccinella septempunctata, the seven-spot ladybird, or seven-spotted ladybug, is the most common ladybird in Europe. In the UK, there are fears that the seven-spot ladybird is being outcompeted for food by the harlequin ladybird.

In the US, this European ladybird has been repeatedly introduced as a biological control. It has been designated the official state insect of Delaware, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Ohio and Tennessee. But there are some ecological concerns surrounding the fact that this species has outcompeted many native species, including other members of the Coccinella family.

What is a great native species in one area can be invasive and a ‘pest’ in another. So it’s always important to think about your geographical location when determining which ladybugs are good in your garden.

How To Attract Wild Ladybugs To Your Garden

Though there are a few exceptions (like the Mexican bean beetle), encouraging native ladybugs is almost always beneficial in your garden. And the more different ladybugs you can encourage, the better.

The first thing to remember when you want to protect native biodiversity is it’s important to garden organically. Chemical controls for pests or weeds can harm all insect life (and other wildlife) in your garden.

When trying to attract predatory insects like ladybugs to your garden, it’s always best to begin by thinking about where you live.

Which ladybugs and other insects are already present in your area? The more you can learn about local wildlife and ecology, the better. A great resource for learning which ladybugs are native to your region is your local agriculture cooperative extension office.

It’s also important to think about the insects themselves. Which will be most effective in balancing the local ecosystem and helping you deal with particular pest species? Which ladybugs will help maintain a diverse and resilient ecosystem in the short-term and long-term?

To attract ladybugs to your garden, you should:

- Not entirely eliminate the pest species they prey on. (It may seem counterintuitive. But attracting a certain number of pest species can actually make it easier to garden organically over time. Ladybugs and other predatory insects will be drawn to a garden with aphids and other pests to feed on. They will then be present to feed on them and help make sure their numbers do not get out of control.)

- Create wilder and more natural corners in your garden where wildlife can flourish undisturbed.

- Sow and grow a wide range of plants to attract ladybug prey and ladybugs.

- Create structures such as ladybug feeders or ladybug hibernation ‘hotels’.

Planting For Ladybugs

There is a wide range of plants you should sow and grow to attract ladybugs to your garden. The plants you should choose can be broadly divided into the following categories:

- Good aphid attractants (and plants that attract other ladybug prey).

- Plants that are good places for ladybugs to lay their eggs and make a good habitat for them to live on.

- Plants that provide nectar as a dietary supplement for ladybugs.

Some plants will fit all three of these criteria, while others may provide some of what a ladybug needs and wants. Broadly speaking, it is best to introduce a good range of plants (including plenty of native plants) with as much variety as possible.

Some great plants for ladybugs include:

Herbs such as:

Flowers such as:

- dandelions

- nasturtiums

- calendula

- marigolds

- Queen Anne’s lace

- alyssum

- cosmos

- statice

- butterfly weed

- bugleweed

Of course, these are just a few examples of the hundreds of plants that will attract and aid ladybugs in your garden.

Remember, it’s important to choose the right plants for the right places and to think about which plants will be best where you live.

Creating a Ladybug Feeder

Planting for ladybugs and attracting their natural prey is the best way to encourage them into your garden and keep them there. But to help out ladybugs when natural food sources are scarce, you could also consider creating a ladybug feeder.

Ladybug Feeder @ apartmenttherapy.com.

Creating a Ladybug Hibernation Zone

Another thing to think about when making your garden a ladybug-friendly zone is where your ladybugs will be able to rest up for the winter. Most ladybugs overwinter as adults. When they go into diapause, they are sluggish and mostly inactive.

They commonly excrete a chemical that attracts other ladybugs to congregate close by. So if you can encourage a few ladybugs to stay in your garden over winter, you may well find that this attracts more that will emerge come spring.

Ladybugs need a moist and sheltered environment that will remain frost-free and ideally above around 55 degrees F. They seek out somewhere which offers a degree of protection against predators.

One good way to encourage overwintering ladybugs in your garden is to leave brush and hollow-stemmed dead plant matter in place so they have a place to hide.

But you can also consider making a ladybug house for these beneficial insects to use.

How To Build a Ladybug House @ wikihow.com.

Making a Ladybird Hotel for Your Garden @ wikihow.com.

Make a Simple Bug or Ladybird Home @ schoolgardening.rhs.org.uk.

Whether or not a ladybug house will be beneficial will depend on where you live and the ladybug species that are found in your area.

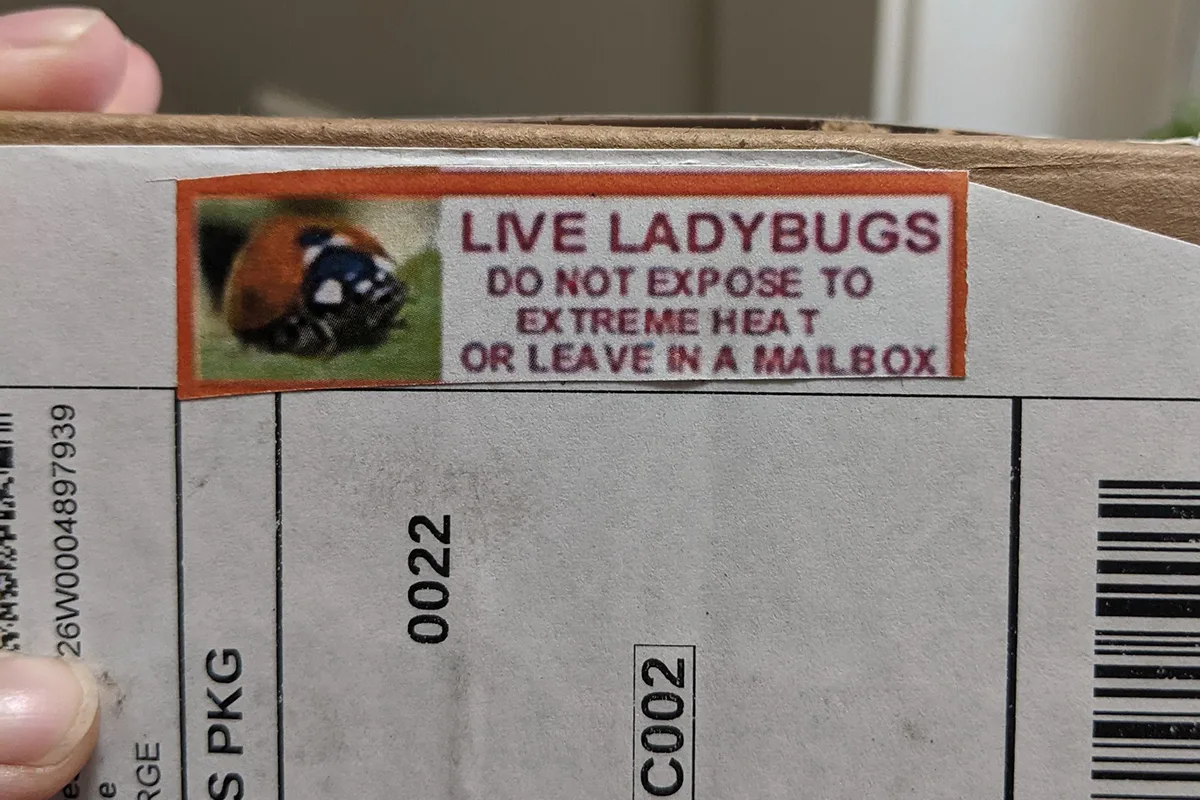

Introducing Ladybugs To Your Garden

If you create a thriving ecosystem with plenty of pests species to prey on and plenty of diverse plant life, it is likely that ladybugs will arrive on their own. But in certain circumstances, the surrounding ecosystem may have been degraded to the point that wild ladybugs in the area are in short supply. In these cases, it may be a good idea to introduce ladybugs to your garden.

Before you decide to introduce ladybugs to your garden, however, think very carefully. It’s always best to try to encourage wild ladybugs to arrive. It is only where such measures have not been successful that you should even consider introductions.

Introducing ladybugs to your garden can also be problematic in a range of other ways. The choices you make can cause more harm than good. So it is very important to make the right decisions.

Choose Native Species

The first thing to get right is the particular ladybug species you choose. Of course, you should always choose a ladybug that is native to your area. Introducing the Harmonia axyridis or European ladybug is common in the US. Unfortunately, as described above, these are non-native. They can cause ecological harm by outcompeting native species.

Avoid Wild-Harvested Ladybugs

Another thing to be aware of is that most of the ladybugs sold in the US are wild harvested. Hippodamia convergens and Harmonia axyridis are all wild harvested, and the only commercially reared ‘red’ ladybugs usually available for home gardeners are Adalia bipunctata and Coleomegilla maculata.

Research has shown that 3–15% of ladybird beetles harvested in the wild carry the internal parasite Dinocampus coccinellae. The same study found many of the harvested beetles to be infected with Microsporidia. This shortens the lifespan of ladybugs and reduces the number of eggs they lay. Introducing ladybugs that are infected could introduce pathogens to wild populations in your area.

To avoid supporting the sale of ladybugs collected in the wild, it is important to choose ‘farmed’ ladybugs from a specialist supplier. You can get tubes of pink spotted ladybug (Coleomegilla maculata) larvae from Insect Lore, for example.

(Remember, ladybugs are not the only predatory insect to consider for biological control. You could also, for example, consider introducing green lacewings for pest control. You can get these from Beneficial Insectary.)

Introduce Larvae, Not Adult Ladybugs

Introducing ladybugs at the larval stage is generally more effective than introducing adult ladybugs during diapause. There are no guarantees that ladybugs introduced as adults will stay on the plants you want them to. Nor is there any guarantee that they will feed on the pests you wish them to.

Many gardeners who introduce ladybugs forget to do the groundwork to ensure that the ladybugs will want to stay. Remember, if your garden fails to attract wild ladybugs, it will likely not be a good environment for introduced ladybugs either.

Introducing native ladybugs may be a solution in certain very limited cases. But generally speaking, it is best to take a more holistic view. You should not think of introducing any species as a ‘quick fix’ but should generally work more broadly to encourage ladybugs (and a range of other beneficial, predatory insects) to your garden.

Read Next:

Get the famous Rural Sprout newsletter delivered to your inbox.

Including Sunday musings from our editor, Tracey, as well as “What’s Up Wednesday” our roundup of what’s in season and new article updates and alerts.